Will low levels of literacy remain a

gerontological issue in Ireland?

Áine Bernadette Mannion

/

How low levels of literacy have impacted older adults and the continued role of policy and lifelong education interventions.

Introduction

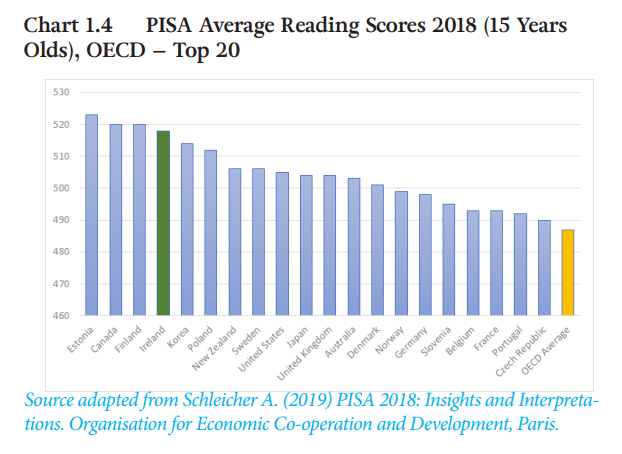

Ireland has a below average literacy rate for adults, with a low ranking of 17th out of 24 OECD countries, and low levels of literacy for older adults can have devastating impacts (CSO 2013). Yet, in the most recent international literacy assessments of 15-year-olds, Ireland ranked 4th in the OECD (Schleicher 2019). Literacy in an Irish context has been related to a cohort effect where over time adult literacy rates are expected to improve (Denny et al. 1999). Nevertheless, this essay will explore how low literacy levels is a gerontological concern with continuing relevance. The impact of low literacy levels on older adults aged 65 years and older will first be explored. The possibility of a cohort effect will also be analysed using the evidence from different cohortspecific international literacy assessments and skills surveys. However, older adults with literacy difficulties are not a homogeneous group, and the most disadvantaged are showing persistent low levels of literacy (Lalor et al. 2009). Therefore, I will look to lifelong education interventions and policy being informed by research that includes older adults, which will remain gerontological concerns regardless of demographic changes. Literacy can be seen as one of the tools needed to fully participate in society and to achieve one’s goals, and is essential in the use of technology, communication skills or numeracy (NALA 2020). However, due to the limited scope of this essay, the evidence put forward here will specifically refer to proficiency in reading and writing.

Is literacy a gerontological concern? How low levels of literacy impact older adults

Low literacy levels have been found in numerous studies to have vast-ranging effects, or costs, on older individuals and their families (Grotlüschen et al. 2016). When Interviewing older adults with literacy difficulties, the National Adult Literacy Agency [NALA] found that respondents were less likely to participate in community activities out of fear their family and friends would think less of them upon finding out they had literacy difficulties (Lalor et al. 2009). The Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing [TILDA] has found among their respondents that those aged 75+ were significantly less confident at filling in medical forms compared to younger 65+ cohorts (Turner et al. 2018; HaPAI 2018). This is reflective of other research that health and social care services can be challenging to navigate for older adults with literacy difficulties, resulting in adverse physical and mental health outcomes, for example, chronic diseases like diabetes, higher mortality rates, and an increased likelihood of dementia (Kaup et al. 2014; Kim et al. 2014; Lamar et al. 2019; Pandit et al. 2009; Rentería et al. 2019; Sudore et al. 2006). From health to social impacts, research on older adults has unanimously shown that low literacy levels can deeply impact in many areas of an older adult’s life.

Ultimately, negative effects of low levels of literacy are not just confined to those aged 65+, however, both the Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies [PIAAC] and TILDA have found that age and more significant literacy difficulties are positively correlated (Barrett & Riddell 2019; Turner et al. 2018; HaPAI 2018). As per Chart 1.1, the average Irish PIAAC scores decrease with age. Older adults in Ireland with literacy difficulties have described how historical abuse during their education negatively impacted on their current literacy proficiency and involvement in lifelong education. They also described becoming very reliant and a burden on family to cope with basic daily literacy tasks, which could become problematic as a family structure changes, for example, a spouse passing away (Lalor et al. 2009). Therefore, ramifications for having low levels of literacy is not solely an issue for the 65+, however there is a distinct experience for older adults.

A Cohort Effect?

Though the ramifications of low literacy are deeply felt, as outlined in the essay so far, some argue that low levels of older adult literacy are just a cohort effect that will correct itself. Population projections show that the number of older adults in Ireland will expand significantly from its last census level of 629,800 in 2016 to nearly 1.6 million by 2051 (CSO 2017b). One could argue that this will make the issue of low levels of older adult literacy more of a concern as society grows older. However, it is alternatively projected that as time goes by, older adults with low literacy levels will be replaced with those with higher levels of literacy, who grew up following the introduction of proactive literacy and education policy interventions (Denny et al. 1999). When comparing the first International Adult Literacy Survey [IALS] in the 1990s with the most recent Irish PIAAC sores, as per Chart 1.2, over time the number of adults at Level 1 or below is decreasing, which are the levels corresponding to low performance. As these demographic changes are realised, issues concerning older demographics may become of greater importance, with the context of literacy concerns demonstrating a strong argument for the inverse of this.

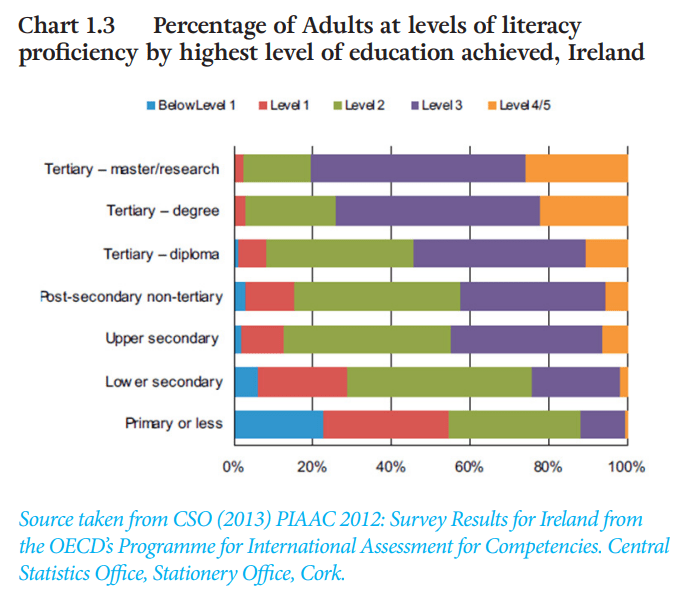

Denny et al. (1999) contend that the introduction of free post-primary school education provides a possible explanation for the cohort effect where literacy levels will improve in time. Ireland’s low competitiveness in international adult literacy rankings as well as this being a phenomenon observed in older people, can be explained by the existence of a cohort of adults who were too old to avail of free post-primary education from 1967. This cohort received less schooling than future cohorts and are behind in both literacy and educational attainment. Chart 1.3 shows Irish PIAAC findings that demonstrate that educational attainment directly correlates with a person’s literacy level. Denny et al. (1999) state that the effect of formal schooling was particularly strong in an Irish context. In 1966, 7% of those aged 14 or older remained in full time education (CSO 1966). Today approximately 90% of 15- to 19-year-olds have completed lower or upper secondary school (CSO 2017a). Those aged 12 in the year the then-controversial policy was introduced, turned 65 years old in 2020. Therefore, with the introduction of secondary school education to explain this cohort effect, we should expect to see improvement over time.

Looking at contemporary assessments of childhood literacy, there is clear evidence of above-average literacy levels compared to older adults, providing evidence of a cohort effect and improvement over time. PISA [Programme for International Student Assessment] tests the literacy and other skills of 15-year-olds. Looking to Charts 1.4 and 1.5 it is possible to see the trend in Irish literacy rates with younger cohorts ranking well above average, unlike Ireland’s PIAAC results which show adults below average. PISA classifies 88% of Irish 15-year-olds as having at least level 2 proficiency in reading, which they consider as the baseline needed to participate effectively and productively in society and future learning (ERC 2017). Again, policy change has been credited with improving literacy levels, for example, the implementation of the National Strategy to Improve Literacy and Numeracy among Children and Young People 2011–2020 (Kennedy 2013). These assessment scores provide evidence of a cohort effect, and as these younger cohorts age, it is logical to expect the levels of literacy of older adults will also increase.

The impact of socio-economic background on literacy

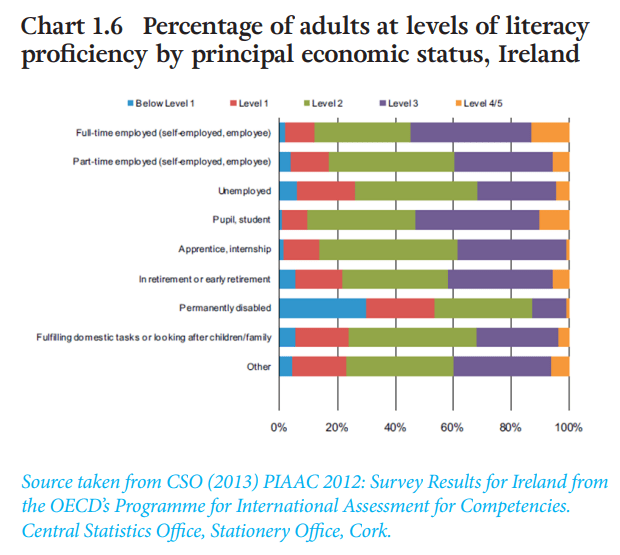

Literacy assessment scores might provide evidence for an argument of a cohort effect but it also promotes a narrative that all cohorts are homogenous groups, despite there being evidence of a different experience for the most disadvantaged. Research by NALA has highlighted the profound and specific experiences of older adults who are members of lower socioeconomic classes, the Irish travelling community, and those who are homeless (Lalor et al. 2009). Western nations still demonstrate profound gaps between the literacy achievement of children in lower socioeconomic backgrounds and their wealthier counterparts (Kennedy 2013). Significant differences for the most economically disadvantaged can be seen for adults in Chart 1.6, but also in the PISA results where 22% of students in DEIS [Delivering Equality of Opportunity in Schools] schools had only very basic reading skills in comparison to 9% of children in non-DEIS schools (Gilleece et al. 2020). Therefore, even as demographics change and absolute literacy levels rise, the most disadvantaged are still facing significant literacy difficulties.

The Role of Interventions: Adult and Life-Long Education

The provision of lifelong education could be an intervention that will remain a vital part of literacy policy for the most disadvantaged in ageing societies, as analysis of literacy outcomes have concluded that education is persistently the most important predictor of literacy proficiency (Desjardins 2003). Adult education interventions can positively impact the literacy proficiency of older adults, however, those who engaged with education to a greater extent in the past are more likely to engage with education throughout their life course (Findsen and Formosa 2011). Bruello et al. (2015) interestingly found that there was a relationship between education and lifetime earnings with how accessible books were in the homes of 10-year-olds. Those with greater access and ability to afford books as children had much higher returns from education. Therefore, adult education and policy that invests in early educational attainment, with a full life course perspective will remain a gerontological concern and necessary literacy policy intervention for the most disadvantaged older adults with low levels of literacy.

Examining how and why lifelong education interventions are provided, and their role within labour markets, will also remain a concern for older adults. Barrett and Riddell (2019) argue that adult education policy is growing in importance because of societies’ ageing demographics, but also because of the changes in the labour market, including changes to the nature of work and retirement ages. However, this also leads to criticisms of adult literacy education as it shifts into a mechanism for meeting the upskilling needs of the labour market which can preclude older people from seeing relevance in such programmes for themselves (O’Brien 2018). A one size fits all approach to success can often focus on perceived deficits rather than supporting positive capabilities and opening up the possibility of personal development and learning for the older adult (Lalor et al. 2009; Findsen & Formosa 2011). The commodification of adult literacy education, therefore, will also remain a concern for older adults with literacy difficulties.

Limitations of literacy policy, assessments and research

Lastly, when discussing if literacy will remain a gerontological concern, it is important to highlight the lack of older adult specific assessments and consequently policy being based on outdated or non-older adult specific data. Literacy rates and statistics are known to be a difficult indicator to analyse, for example, the reliability of some countries’ literacy rates and testing practices have been questioned (Zhao 2020). The only major assessment of adult literacy, PIAAC, is nearly a decade old. Though a new wave is expected within the next two years, PIAAC testing does not involve those aged over 65. Much of the analysis of the older adult literacy trends and the majority of the adult and older adult education and literacy policy is based on PIAAC results (NALA 2020; Lalor et al. 2009; Barrett & Riddell 2016). It is also important to note that no two test items are the same in PIAAC and PISA, which raises questions for the legitimacy and speculative nature of cohort comparisons of literacy rates (CSO 2013). Therefore, the quantity and quality of data and evidence-based policy relating to the distinct experience of older adults with literacy difficulties will remain a gerontological concern.

Conclusion

Ultimately, low levels of literacy will remain a gerontological issue in Ireland. It is a gerontological concern because of the deep and

devastating social and health impacts literacy difficulties can have on older adults. Certainly, there has been great and continued improvement of Irish literacy levels, with evidence of a cohort effect as younger cohorts who availed of proactive literacy and education policy innovations age. However, despite improvements there are still significant gaps in literacy levels that correlate with socio-economic status. As older adults and those with literacy difficulties are not a homogenous group, evidenced-based literacy policy and considered life-long education interventions will continue to be a gerontological issue in Ireland.

Bibliography

Barrett G. & Riddell W.C. (2016) Ageing and Literacy Skills: Evidence from IALS, ALL and PIAAC. IZA Institute of Labor Economics, Bonn.

Barrett G.F. & Riddell W.C. (2019) Ageing and skills: The case of literacy skills. European Journal of Education 54(1), 60–71.

Brunello G., Weber G. & Weiss C.T. (2015) Books Are Forever: Early life conditions, education and lifetime earnings in Europe. The Economic Journal 127, 271–296.

CSO (1966) Census of The Population Ireland: Education. Central Statistics Office, Stationery Office, Dublin.

CSO (2013) PIAAC 2012: Survey Results for Ireland from the OECD’s Programme for International Assessment for Competencies. Central Statistics Office, Stationery Office, Cork.

CSO (2017a) Census of Population 2016 – Profile 10 Education, Skills and the Irish Language: Level of Education. Central Statistics Office, Cork. Retrieved from http://www.cso.ie on 6 Jan 2021.

CSO (2017b. Population and Labour Force Projections 2017 – 2051 [online]. Central Statistics Office. Central Statistics Office, Cork. Retrieved from http://www.cso.ie on 6 Jan 2021.

Denny K., Harmon C., McMahon D. & Redmond S. (1999) Literacy and Education in Ireland. The Economic and Social Review 30(3), 215–226.

Desjardins R. (2003) Determinants of literacy proficiency: a lifelong-life wide learning perspective. International Journal of Educational Research 39, 205–245.

ERC (2017) Proficiency levels in assessments of Reading and Mathematics. Education Research Centre, Dublin. Findsen B. & Formosa M. (2011) Lifelong Learning in Later Life: A Handbook on Older Adult Learning. Sense Publishers, Rotterdam.

Gilleece L., Nelis S.M., Fitzgerald C. & Cosgrove J. (2020) Reading, mathematics and science achievement in DEIS schools: Evidence from PISA 2018. Educational Research Centre, Dublin.

Grotlüschen A., Mallows D., Reder S. & Sabatini J. (2016) Adults with Low Proficiency in Literacy or Numeracy. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Paris.

HaPAI (2018) Positive Ageing Indicators 2018. Healthy and Positive Ageing Initiative, Health Service Executive’s Health and Wellbeing Division, Department of Health, Age Friendly Ireland, Atlantic Philanthropies, Dublin.

Kaup A.R., Simonsick, E.M., Harris T.B., Satterfield S., Metti A.L., Ayonayon H.N., Rubin S.M. & Yaffe K. (2014) Older Adults With Limited Literacy Are at Increased Risk for Likely Dementia. Journals of Gerontology: Medical Sciences 69(7), 900–906.

Kennedy E. (2013) Literacy Policy in Ireland. European Journal of Education 48(4), 511–527.

Kim B.-S., Lee D.-W., Bae J.N., Chang S.M., Kim S., Kim K.W., Rim H.-D., Park J.E. & Cho M.J. (2014) Impact of illiteracy on depression symptomatology in community-dwelling older adults. International Psychogeriatrics 26(10), 1669–1678.

Lalor T., Doyle G., McKenna A. & Fitzsimons A. (2009) Learning Through Life: A Study of Older People with Literacy Difficulties in Ireland. The National Adult Literacy Agency, Dublin.

Lamar M., Wilson R.S., Yu L., James B.D., Stewart C.C., Bennett D.A. & Boyle, P.A. (2019) Associations of literacy with diabetes indicators in older adults. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health 73, 250–255.

NALA (2020) Literacy Now: The Cost of Unmet Literacy, Numeracy and Digital Skills Needs in Ireland and Why We Need To Act Now. National Adult Literacy Agency, Dublin.

O’Brien T. (2018) Adult literacy organisers in Ireland resisting neoliberalism. Education + Training 60(6), 556–568.

Pandit A.U., Tang J.W., Bailey S.C., Davis T.C., Bocchini M.V., Persell S.D., Federman A.D. & Wolf M.S. (2009) Education, literacy, and health: Mediating effects on hypertension knowledge and control. Patient Education and Counselling 75, 381–385.

Rentería M.A., Vonk J.M.J., Felix G., Avila J.F., Zahodne L.B., Dalchand E., Frazer K.M., Martinez M.N., Shouel H.L. and Manly J.J. (2019) Illiteracy, dementia risk, and cognitive trajectories among older adults with low education. Neurology 93, e2247-e2256.

Schleicher A. (2019) PISA 2018: Insights and Interpretations. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Paris.

Sudore R.L., Yaffe K., Satterfield S., Harris T.B., Mehta K.M., Simonsick E.M., Newman A.B., Rosano C., Rooks R., Rubin, S.M. Ayonayon H.N. & Schillinger D. (2006) Limited Literacy and Mortality in the Elderly: The Health, Aging, and Body Composition Study. Journal of General Internal Medicine 21, 806–812.

Turner N., Donoghue O., and Kenny R.A., (eds.) (2018) TILDA Wave 4: Wellbeing and Health in Ireland’s over 50s 2009-2016. The Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing, Dublin.

Zhao Y. (2020) Two decades of havoc: A synthesis of criticism against PISA. Journal of Educational Change 21, 245–266.