“Magnanimous or Marauding? Towards a New Framework of Aberrant Insurgent Violence Against Civilians.

Dylan Jones

/

Abstract

It is often taken as inevitable that civilians suffer violence at the hands of insurgent groups. This is misleading; there are huge discrepancies in the levels of violence across these conflicts. In some cases, insurgents inflict violence brutally and indiscriminately on civilian populations, while in others, civilians are explicitly protected or selectively targeted in limited cases. This paper seeks to understand the underlying causes of this profound divergence. It is argued that insurgencies with high economic endowment commit violence at a higher rate than those with low economic endowment, although the latter is also likely to commit violence against civilians if and only if they expose a ‘hardline’ ideological approach towards issues of security. The policy implications of this project are self-evident; International and Non-Governmental Organisations will be better equipped to protect civilians in danger of insurgent violence if the typology of which insurgencies are liable to commit such acts is better understood.

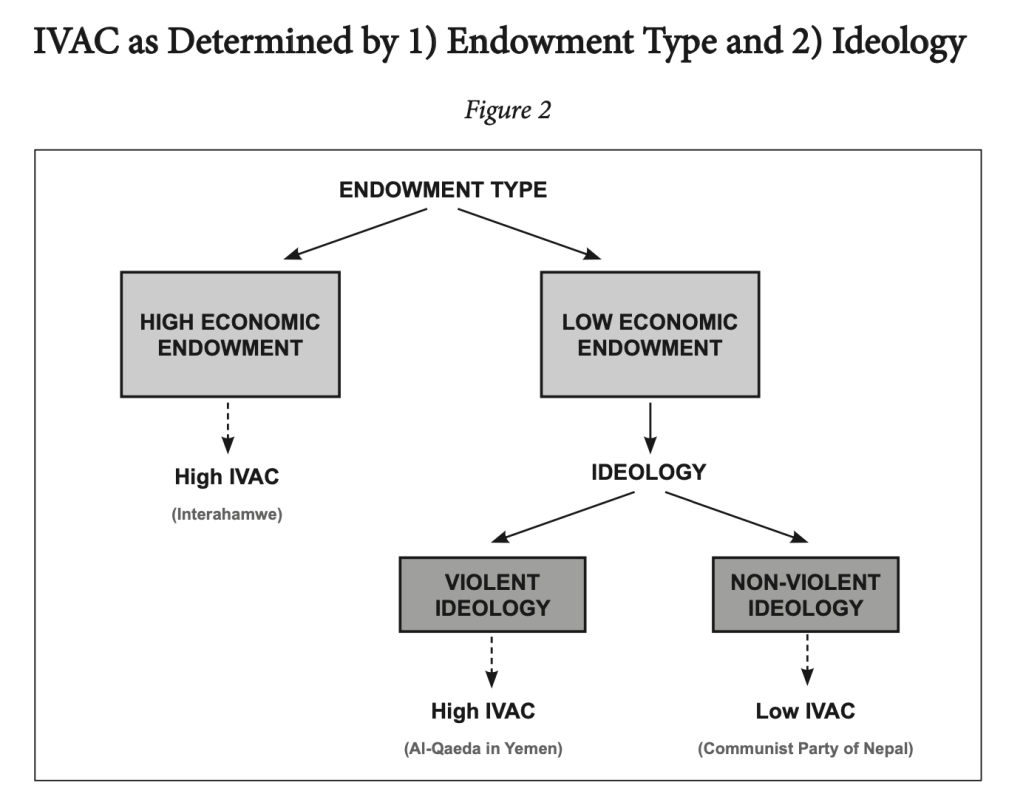

Despite claims of global humanitarian progress, one million civilians have been deliberately killed by armed groups during civil conflicts in the last 30 years (Pettersson and Öberg, 2020). Notwithstanding a swathe of new research, our current understanding of inter-insurgency variation of insurgent violence against civilians (and the broader problem of predicting insurgent behaviour) remains unsatisfactory. Many theories adequately point to either individual or systemic factors, but a lack of integration often leaves us blind to scenarios in which they overlap (and, importantly, those in which they do not). Despite calls to leave behind the substantial ‘macro- and micro-level divide’ that dominates the literature (Balcells and Stanton, 2021), conceptual frameworks for understanding these processes nevertheless tend to concern one or the other. This paper, therefore, seeks to propose a model of variant Insurgent Violence Against Civilians (henceforth IVAC) incorporating two variables: resource endowment (macro-level) and ideology (micro-level), aiming to synthesise the theories of Weinstein (2009) and Leader Maynard (2022), using the theoretical strength of the former, but bolstering it with the unwieldy but substantial explanatory power of the latter. This paper argues that when economic endowment is high, insurgencies commit high levels of IVAC. In contrast, when economic endowment is low, the IVAC committed by insurgencies depends on their ideological approaches to security politics; insurgencies with ‘hardline’ ideologies are more likely to commit IVAC than those with ‘limitationist’ ideologies.

The following paper begins by examining Weinstein’s theory and argues that although broadly correct, it cannot convincingly operate without ideology as an implicit causal mechanism (giving credence to the suggestion to explicitly include it). Subsequently, it will examine Leader Maynard’s theory of ideology in explaining mass killing, explaining the deficiencies in taking it as a ‘first port of call’. Following this, a subset argument is employed, demonstrating that Weinstein’s exclusion of ideology from his model leaves him unable to comment on the empiric fact of vastly divergent levels of IVAC between similarly-endowed groups (using Al-Qaeda in Yemen and the Communist Party of Nepal as contrasting case studies). This highlights the need to integrate the two theories, using Maynard’s as a secondary explanatory variable that helps in both reinforcing the causal mechanisms for Weinstein’s theory and in giving further predictive power in the subset of groups with low economic endowment.

Weinstein – Resource Endowment

Weinstein argues that disparate IVAC is caused by the endowments that insurgent leaders have at their disposal at the outset of their movement. He describes a ‘resource curse’ (Weinstein, 2005, p 598) analogous to that which resource-rich states sometimes face; if insurgency leaders have high economic endowment, this can be used to recruit and motivate insurgents to join the cause. This endowment can manifest itself in numerous ways; for example, an insurgency may have control of valuable assets and their trade, most commonly goods such as oil or narcotic plants. Other versions of economic endowment may be liquid capital generated from taxation, which is common among insurgencies headed by warlords (Azam, 2006), or from foreign support from state or non-state actors (such as diaspora communities). Economic endowment can even be as simple as the ability to effectively loot resources from nearby populations. The recruits attracted by any variant of economically endowed insurgencies are categorised as consumers by Weinstein; they are not motivated by the cause itself but rather by immediate material benefits that can be reaped through their involvement in the insurgency (Weinstein, 2009, p 102). Such insurgencies are, therefore, demarcated as opportunistic rebellions. In such cases, we see high levels of IVAC as recruits are uncommitted, motivated by self-gain, and seek to continually extract resources from civilians. This paper borrows Weinstein’s broad definition of violence, which includes not only homicide but looting, coercion, and all forms of sexual violence (ibid. p 199-200). High IVAC is thus attributed to insurgencies who commit such acts at a high frequency and/or in high intensity. In opportunistic rebellions, higher-ups must permit (or at least tolerate) such behaviour in order to retain their military capacity (ibid. p 10). Other research has confirmed that behaviour like looting is self-perpetuating (looting begets looting), as it disincentivises production among small communities, leading former producers to begin looting too (Azam and Hoeffler, 2002). Although violence may be indiscriminate, it is nonetheless strategic. The finding that civilian violence is always strategic, that civilian harm is not simply ‘collateral damage’, is widely shared throughout the literature (Azam, 2006; M Wood, 2010; Valentino, 2014). Weinstein’s conclusion that economic endowment leads to increased IVAC is similarly widely accepted, even by those who posit different causal explanations (Sarkar and Sarkar, 2016).

Alternatively, where economic endowments are not present, insurgency leaders cannot offer would-be insurgents immediate material benefits. Instead, they recruit using social endowments, specifically pre-existing ethnic, religious, or ideological ties. Potential recruits are guaranteed utility, whether that be power, capital, or structural change, if and only if the insurgent group is successful in their aims. Thus, these insurgents are investors; they are significantly more dedicated to the cause of the insurgency than their consumer counterparts. Weinstein denotes these as activist rebellions (Weinstein, 2009, p 10). Due to resource limitations, activist insurgencies have to rely on civilian populations for goods, including shelter, arms, and provisions. They can make up their resource deficit by striking cooperative bargains with civilians (ibid.). They are, therefore, disincentivised to commit violence against civilians.

For pragmatic purposes, such insurgencies will henceforth be referred to as low endowments (although social endowments are usually high).

Although Weinstein may construct his model without reference to ideology, it is nonetheless implicitly included. In low-endowment contexts, ideology is a necessary motivator for activist insurgencies. For example, cases of ethnic ties should also be encompassed under Maynard’s conception of ideology as “distinctive political worldviews” (Maynard, 2022, p. 17); it is a distinctly political worldview to view ethnic divides as salient, to suggest that groups are fundamentally different, and to believe that members of such a group should cooperate. Similar argumentation can be used for other manifestations of social ties, such as class or religion (justification for viewing religious ties as ideological is presented later).

Weinstein’s theory, although causally credible and supported by significant empirical backing, is nonetheless imperfect; as he himself speculates, it “may be too simple” (Weinstein, 2009, p. 327). The primary reason for this is its strict dyadism; it cannot explain altering behaviour within the subset of low endowment, an empiric reality which this paper attempts to illustrate. While it is widely held that economic variables are the main driver of the insurgency itself (Collier and Hoeffler, 2004), it should be clear from the empirical examples below that an absence of political and social variables paints a highly imperfect picture of behaviour within those insurgencies.

Despite what Weinstein may assert, IVAC is not consistent among insurgencies with low economic endowment. This paper will focus on two cases: firstly, the Communist Party of Nepal, which, in accordance with Weinstein, uses violence seldomly, and secondly, Al-Qaeda in Yemen, a movement that subverts Weinstein’s prediction, committing high levels of IVAC, despite having undeniably low endowment. In order to understand this discrepancy, we shall turn to Leader Maynard’s concept of ideology’s role in mass killing.

Leader Maynard – Ideology

This paper, along with Leader Maynard’s book, diverges from the majority of the political violence literature in taking ideology seriously as a rigorous explanatory variable; this literature tends to over-emphasise economic variables (Collier and Hoeffler, 2004) to the detriment of equally effectual social and political ones, making ideology a particularly ‘unfashionable’ approach to explaining the social world. This is, on some level, understandable; it, in particular, is a notoriously difficult concept in the soft sciences. Issues arise in creating a practical, predictive theory, even if one agrees on the fact of what it is (presupposing, of course, that it is at all). Major disagreements originate in the simple question of whether our conception of ideology is narrow or wide.

Firstly, there are obvious issues with narrow conceptions of ideology. Such ‘traditional ideological perspectives’ (sometimes called ‘true believer’ models) are extensively criticised by Maynard (2022, pp. 30–32). They conceptualise ideology as a rigid, unchanging, and systematic worldview. This is unhelpful; rigid definitions of ideology (denoted by labels such as ‘liberal’ or ‘fascist’) are wildly inconsistent predictors of group behaviour. We need only look to Weinstein’s (2009, pp. 81–95) discussion on the differing conduct of two distinct branches of the Sendero Luminoso, firstly in Peru’s southern highlands and secondly in the Amazonian jungle. Despite both factions identifying as Maoist (an undeniably ideological self-demarcation), their behaviours are highly contrasting. While the former created institutions and protected civilians, using violence only to further their political aims (ibid., p. 88), the latter, due to its economic endowment of access to large coca plantations and thus a lucrative drug trade, exerted restrictive control over civilians, wielding violence far more often, and far more indiscriminately (ibid., p. 95). Evidently, ideology in this narrow sense cannot and should not be used as a primary unit of analysis, as even sects of the same ideologically labelled movement act in highly disparate ways.

Maynard (2022, p. 4) therefore rejects this conception. Instead, he proposes a ‘neo-ideological’ model. Here, ideologies are less easily quantified, defined as “distinctive political worldviews” (ibid., p. 17). This is far more accurate; ideology is a nebulous concept, affecting a presumably incalculable range of positions and actions. For Maynard, however, the necessary facet of ideology that pertains to violence is its function in producing ‘justificatory narratives’ (ibid., p. 5). These create the necessary conditions for violence before, during, and after the act itself by perverting familiar notions of security politics (the need for certain measures to ensure the protection and flourishing of the state or movement) in times of crisis into justification for violence. Specific examples of justificatory mechanisms range from threat construction, in which certain individuals are deemed dangerous and thus retaliation operates as self-defence (ibid., p. 154), to deidentification, in which the shared identity between in-group and out-group is denied or suppressed (ibid., p. 161).

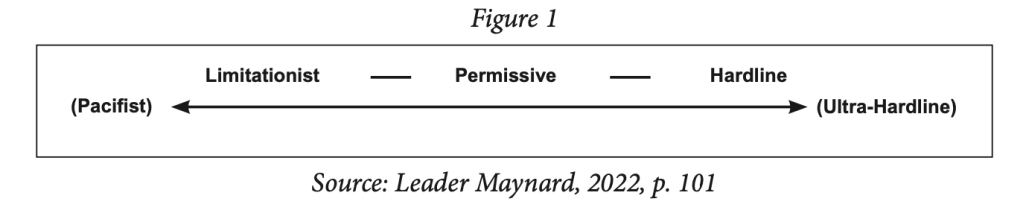

An organisation that is liable to act in such a way is characterised as pushing a ‘hardline’ ideology (ibid., p. 98). Alternatively, ‘limitationist’ ideologies portray violence as ineffective, costly, and normatively undesirable (ibid., p. 100). Thus, the salient difference in ideology that explains mass killing is not a traditionally simplistic social or economic left-right axis but rather an axis that measures diverging approaches to security politics, placing limitationist policy on the left and hardline policy on the right, with poles defined as the extremes of total pacifism and ultra-hardline.

Although Maynard exclusively focuses on mass killing (ibid., p. 46), the same mechanisms simultaneously function in explaining the occurrence of lower-intensity manifestations of IVAC, such as homicide, rape, looting and coercion. Thus, the further to the right of the above spectrum an insurgency falls, the more likely it is to commit high levels of IVAC, even if they have low endowment. It should be noted that further left (more limitationist) ideologies and further right (more hardline) ideologies are later referred to by their consequent characters as non-violent and violent ideologies, respectively.

While compelling, this account scarcely resembles a theory; it is descriptive, not prescriptive. Its inductive nature limits its predictive power; by explaining everything [that ideology can do], it precludes us from predicting anything (Waltz, 2004, p. 3). To illustrate this, we can examine Maynard’s discussion of Interahamwe leader Juvénal Habyarimana, who was popular amongst his militants for promising “jobs and good times” (Maynard, 2022, p. 279). This is an obvious example of the power of high-endowment movements to create highly violent outcomes without the need for ideology.

This illustrates two crucial facets of this paper’s argument. The first is that ideology is not essential in motivating violence in high-endowment contexts (thus, this subset is excluded in the revised model below). The second is that wide conceptions of ideology, like Maynard’s, should not be used as our ‘first port of call’, as the concept is too unwieldy and nebulous and can be used to derive what is quite simply the ‘wrong explanation’ of almost any occurrence. Using Maynard’s conception, we could validly assert that this behaviour was ideologically driven, that the pursuit of capital (or even utility) at the detriment of civilians was a hardline ideological perspective created by Hutu elites and justified through propaganda. Yet, while plausible, this is an inaccurate way to view the phenomenon. Maynard’s theory, in its current conception as a ‘first port of call’, is essentially unfalsifiable (Popper, 1963). Thus, it should be evident that ideology, especially the neo-ideological view proposed by Maynard, undeniably affects IVAC. However, this wide conception of ideology is overly permissive; it ‘lets too much in’. We, therefore, cannot use it as our primary unit of analysis. It does, however, function well in explaining discrepant IVAC among low-endowment insurgencies (the major flaw in Weinstein’s theory), as the following sections will illustrate.

Accordingly, we will now examine two contrasting case studies to demonstrate that Weinstein’s theory, due to its exclusion of ideology, fails to predict huge discrepancies in similarly endowed but ideologically differing groups: the Communist Party of Nepal and Al-Qaeda in Yemen.

Communist Party of Nepal

The Communist Party of Nepal (CPN) refers here to the Nepalese Maoist social movement and later mainstream political party (although the name is also used by a related but non-aligned Marxist-Leninist party). The CPN is a quintessential example of a low-endowment group; the poverty of the areas in which the group originated both informed their ideological mission and prevented them from attracting ‘consumer’ militants (Hachhethu, 2009, pp. 48–49); recruits could not gain material benefits quickly, and therefore had to be committed to the long-term advancement of the cause, whether for ideological reasons or simply for economic and political benefit, which would only occur after a sustained commitment to the movement’s aims as a whole (Weinstein, 2005, p. 10).

The CPN, as predicted, are highly selective in the use of IVAC; despite launching a lengthy guerrilla warfare campaign, sometimes in highly populated areas (Sijapati, 2004), they are estimated to have killed “fewer than 1,000 people in nearly 10 years of fighting” (Weinstein, 2009, p. 5), exactly as Weinstein’s model predicts. This (relatively) pacifist approach towards citizens (with violence targeted directly at state instruments) was not exclusively a rationalist choice based on material constraints; it was a normative, ideologically informed choice from insurgent leaders, who held strong preferences for a peaceful transition to power (Ogura, 2008, p. 45), and thus should be considered as limitationist, on the left of the spectrum in Figure 1.

Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula

The Yemeni branch of Al-Qaeda, which self-identifies as Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), is a similarly low-endowment group. Al-Qaeda’s ideology has been described as significantly stronger than its material capacity and, thus, its ability to threaten international security (Bugeja, 2015). Their success in mobilising militants has emanated from their ability to exploit social norms, such as religion and ethnicity, to mobilise recruits (International Crisis Group, 2017). However, we see contrasting behaviour to that which Weinstein’s model would predict for such a lowly endowed group; instead of limited violence, we find high levels of IVAC (Carboni and Sulz, 2020).

Although it has been argued that the social endowments utilised by AQAP are explicitly tribal or ethnic rather than ideological (Batal al-Shishani, 2010), this view is likely a remnant of outdated primordialist thought. Research has shown that such divides (in and of themselves) are rarely the cause of political violence (Fearon and Laitin, 2000). Instead, it is elite activation that makes these divides salient (Posen, 1993), namely through processes like deidentification, as described by Maynard (2022, p. 161). AQAP’s name itself elucidates this ideological activation; Salafi-jihadist ideologues like Faris al-Zahrani urge to cast off “colonial divisions” and focus on the links between “proud tribes, who God has favoured with Islam” (Batal al-Shishani, 2010, p. 7), thus the stress on Arabian Peninsula, not Yemen.

One may argue that AQAP’s social endowment is, in fact, derived from religion, not ideology. However, this paper suggests that doing so creates a false dichotomy; if using Leader Maynard’s definition of ideologies as “distinctive political worldviews” (Maynard, 2022, p. 17), religion should instead be conceptualised as a subcategory under ideology. This approach has considerable precedent in political sociology, particularly in the work of Marxist theorists such as Gramsci (Forlenza, 2019). Proving such a view is certainly beyond the scope of this paper, yet even if one is unwilling to accept that all religions disseminate a “distinctive political worldview”, AQAP’s fundamentalist interpretation of the Quran undeniably does, explicitly teaching its followers that “violent jihad is the only way to protect the Islamic world” (Vasiliev and Zherlitsyna, 2022, p. 1241).

Weinstein fails to consider that AQAP is reliant only on those civilians proximate to insurgents. It is rational and strategic to commit violence against civilians physically removed from AQAP, like those in neighbouring or western states. Like CPN, AQAP use violence selectively in order to fulfil their aims. However, unlike CPN, these aims are informed by a particularly violent ideology, one that interprets ideas of security and self-preservation (of a distinctly Islamic worldview) in a particularly hardline manner. Therefore, despite AQAP’s low endowment, this manifests as high levels of IVAC.

Synthesised Model

As has been demonstrated, within low-endowment groups, ideology has an inextricable role in determining IVAC levels. Although this paper does not have the scope to formalise a theory for using ideology as a predictive variable under the low-endowment subset, it should be summarised as such: in the case of low-endowment groups, violence of ideology affects IVAC. If a low-endowment insurgent group is constructed around a violent or hardline ideology, we will find high IVAC (as seen in AQAP). If a low-endowment group is constructed around a non-violent or limitationist ideology, we will find low IVAC (as seen in CPN). This model is visualised in Figure 2 below.

Thus, by using Maynard’s conception of ideology as a causal mechanism within Weinstein’s strict dyadic theory and applying it explanatorily only in the low-endowment subset, ideology can be validly incorporated into resource-endowment theory without sacrificing said theory’s simplicity and predictive value. This allows it to function effectively as an “instrument … useful in explaining what happens in a defined realm of activity” (Waltz, 2004, p. 2). Ideology is importantly considered as secondary to endowment type in the temporal chain of causality due to the issues with using it as a ‘first port of call’, as explained above. This model is, therefore, still predictive, yet more nuanced and dynamic, granting the theory greater explanatory power.

It is, however, in its current state, an ‘informal’ model. Undoubtedly, a brief classification of two case studies has certain limitations; it would be a severe overestimation to affirm the universality of the given argument on such limited research. However, this paper is instead aimed specifically at establishing that the current models for explaining aberrant IVAC levels fall flat. Case studies, both greater in number and in detail, which, as previously noted, are outside this paper’s scope, would be beneficial in confirming the validity of the model. Further research must be undertaken in addition to this, namely confirming empirically the causal mechanism proposed by Maynard and the explicit quantification of both variables, in order to transition this paper’s proposal into a formal model, which should, if the theory is correct, make accurate predictions concerning which insurgencies are likely to commit IVAC.

Conclusion

This paper has presented a more comprehensive model for explaining disparate levels of insurgent violence against civilians, using Weinstein’s resource endowment framework but including ideology as a secondary deciding variable under the subset of low-endowment groups. This is supported by a sharp distinction between two case studies, the Communist Party of Nepal and Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, as informed by their disparate ideological views, borrowing the broad neo-ideological lens used by Leader Maynard. If successful, it is believed that this model will move us towards a more comprehensive understanding of insurgent violence against civilians, allowing the global community to work towards the protection of innocent civilians or innocence in danger around the world.

Bibliography

Azam, J.-P. and Hoeffler, A. (2002) ‘Violence against civilians in civil wars: Looting or terror?’, Journal of Peace Research, 39(4), pp. 461–485.

Azam, J.-P. (2006) ‘On thugs and heroes: Why warlords victimize their own civilians’, Economics of Governance, 7(1), pp. 53–73.

Balcells, L. and Stanton, J.A. (2021) ‘Violence against civilians during armed conflict: Moving beyond the macro- and micro-level divide’, Annual Review of Political Science, 24(1), pp. 45–69.

Batal al-Shishani, M. (2010) ‘An assessment of the anatomy of al-Qaeda in Yemen: Ideological and social factors’, Terrorism Monitor, 8(9), pp. 51–55.

Bugeja, M. (2015) Al-Qaeda in Afghanistan: Nation-building and combating al-Qaeda’s ideology. Hamburg: Anchor Academic Publishing.

Carboni, A. and Sulz, M. (2020) The Wartime Transformation of AQAP in Yemen. ACLED. Available at: https://acleddata.com/2020/12/14/the-wartime-transformation-of-aqap-in-yemen/

Collier, P. and Hoeffler, A. (2004) ‘Greed and grievance in civil war’, Oxford Economic Papers, 56(4), pp. 563–595.

Fearon, J.D. and Laitin, D.D. (2000) ‘Violence and the social construction of ethnic identity’, International Organization, 54(4), pp. 845–877.

Forlenza, R. (2019) ‘Antonio Gramsci on religion’, Journal of Classical Sociology, 21(1), pp. 38–60.

Hachhethu, K. (2009) ‘The Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist): Transformation from an insurgency group to a competitive political party’, European Bulletin of Himalayan Research, 33(34), pp. 39–71.

International Crisis Group (2017) Yemen’s al-Qaeda: Expanding the Base. Available at: https://www.crisisgroup.org/middle-east-north-africa/gulf-and-arabian-peninsula/yemen/174-yemen-s-al-qaeda-expanding-base

Leader Maynard, J. (2022) Ideology and Mass Killing: The Radicalized Security Politics of Genocides and Deadly Atrocities. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

M Wood, R. (2010) ‘Rebel capability and strategic violence against civilians’, Journal of Peace Research, 47(5), pp. 601–614.

Ogura, K. (2008) ‘Seeking state power: The Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist)’, Berghof Research Center for Constructive Conflict Management, 3. Available at: https://idl-bnc-idrc.dspacedirect.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/3a9b00dc-f9ec-4249-befa-563b6989adac/content

Pettersson, T. and Öberg, M. (2020) ‘Organized violence, 1989–2019’, Journal of Peace Research, 57(4), pp. 597–613.Popper, K.R. (1963) Conjectures and Refutations: The Growth of Scientific Knowledge. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Posen, B.R. (1993) ‘The security dilemma and ethnic conflict’, Survival, 35(1), pp. 27–47.

Sarkar, R. and Sarkar, A. (2016) ‘The rebels’ resource curse: A theory of insurgent–civilian dynamics’, Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 40(10), pp. 870–898.

Sijapati, B. (2004) A Kingdom Under Siege: Nepal’s Maoist Insurgency, 1996 to 2003. London: The Printhouse.

Valentino, B.A. (2014) ‘Why we kill: The political science of political violence against civilians’, Annual Review of Political Science, 17(1), pp. 89–103.

Vasiliev, A.M. and Zherlitsyna, N.A. (2022) ‘The evolution of Al-Qaeda: Between regional conflicts and a globalist perspective’, Herald of the Russian Academy of Sciences, 92(S13), pp. S1240–S1246.

Waltz, K. (2004) ‘Neorealism: Confusions and criticisms’, Journal of Politics and Society, 15(1), pp. 2–6.

Weinstein, J.M. (2005) ‘Resources and the information problem in rebel recruitment’, Journal of Conflict Resolution, 49(4), pp. 598–624.

Weinstein, J.M. (2009) Inside Rebellion: The Politics of Insurgent Violence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.